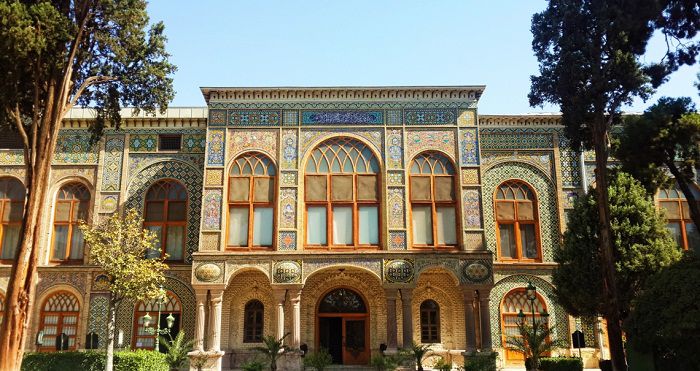

Chehel Sotun, Hasht Behesht, and Talar-e Ashraf, along with several other, less sumptuous buildings are the few survivors of the magnificent compound of Safavid palaces which used to occupy a vast area from Naqsh-e Jahan Square to Chahar Bagh Avenue. These palaces stand amid . superb parkland, which, however, has been largely diminished compared to the original garden of Jahan Nama that had been planted there by Shah Ismail Safavid. Today the original plan of the park and its pavilions, reportedly worked out by Sheikh Bahai, has been distorted by modern modifications, but what remains is still very remarkable.

Chehel Sotun garden covers an area of 67,000 sq. m. The palace 1, occupies about 2,125 sq. m and is fronted by a pool 2,measuring 110 by 16 m. By western standards, Chehel Sotun may seem a relatively small building, but its height of about 15 m and the elegance of the slender columns increase the structure’s grandeur.

Chehel Sotun was conceived by Shah Abbas the Great as a small pleasure pavilion. This now constitutes the Throne Hall 3, of the building and several flanking rooms. Some historical books mentioned that Shah Abbas I celebrated Nouruz of the year 1614 in this palace.

The elegant porch, superb mirror hall 4, and renowned mural paintings were added to the pavilion during the reign of Shah Abbas II. At that time, the palace was used exclusively as a place for entertaining foreign dignitaries. Two historical inscriptions in verse from the Safavid period reveal the long and turbulent history of the building. Both were uncovered from under a plaster layer during archaeological research in 1949. The first, a shorter one, is carved on a pink background.

It mentions the name of Shah Abbas II and the date of the building’s completion (1647). The second, a longer one, this time in stucco letters against a blue background, describes the restoration of the palace during the reign of Shah Sultan Hossein Safavid. It is said that during a feast the building flared up, but it was still possible to extinguish the fire. However, Shah Sultan Hossein, infamous for his excessive piety, saw divine intent in this act and let most of the building burn away. preferring to restore it later. Chehel Sotun shares many traits with Achaemenid architecture. though it seems fairly restrained compared to the excesses of its predecessors. Like the grand structures of Persepolis, it stands on an elevated platform, conforming to the ancient tradition that royal palaces have to soar above the ground. The magnificent porch of the palace also echoes a peristyle that traces its history as far back as the Achaemenid period.

The name of Chehel Sotun (“Palace of Forty Columns”) was given to the building because of the multiple pillars of its elegant porch 4, (“forty” is a common term in Iran to indicate a large but imprecise number). However. by chance the twenty columns of the porch reflected in the pool in front of the building presented a clear sight of forty columns, and many believe that this is the explanation for the name of the palace. Of the twenty pillars of the porch. two are found in the recess that leads to the Throne Halle. Each of the slender pillars is formed of a tree trunk over which a thin layer of colored board has been fitted. In the 17th century. this veneer was covered with colored studs of glass and mirror. What we see today are the decorations that were added during the palace’s rebuilding after the fire of 1706 or during the Qajar period. Today the columns, stripped of their original glass cover, are painted red. They support a light wooden ceiling. With its exposed beams, wide fretwork louvers. and inlaid-work, this ceiling is probably the finest example of this kind in Iran.

Bagh e Chechel Sotun general view

In the centre of the porch is a handsome marble basin 6, highlighted by figures of four lions. These lions are engraved in such a way that every two lions have a common head. They serve as the base for four central columns and, at the same time, spout water into the tank. To preserve the fragile structure, the fountains are in operation only on special Occasions. Before entering the opulent Throne Hall, the visitor should not miss the window above the entrance door. Until recently, the ancient Koran bearing the stamp of the third Shiite Imam was kept there. According to the Islamic tradition, luck will accompany those travelers who have passed under the Sacred Book. Today this Koran is exhibited in the museum of Chehel Sotun. The Thone Hall has glittering ceiling vaults. The walls are painted with both figurative and abstract designs and are decorated with stucco and brightly colored inlaid rosettes. The plasterwork in low relief is colored in rich ultramarine and cobalt blue. vivid scarlet, pale emerald, and solid gold – all woven into intricate and exquisite patterns of great splendor. The hall is in a good state of preservation, and where necessary, restoration has been judiciously carried out. Like the Throne Hall of Ali Qapu, the hall of Chehel Sotun is also adorned with frescos. It is perhaps the best place to study Persian secular art, whose best samples are presented here. In contrast to the pastel and calico motifs of Ali Qapu, the murals of Chehel Sotun have been done with much bolder colors. Here portraits of kings, battle scenes, and royal festivals are depicted in bright, vivid hues on the upper parts of the walls. The lower portions exhibit small genre paintings in the traditional miniature style. All the pictures (except for two paintings known as Chaldoran and Kamal wars which belong to the Qajar era) date from the period of Shah Abbas II.

The paintings of the western wall (opposite the entrance) depict, from right to left. the following subjects:

-The feast given by Shah Abbas the Great in honor of King Vali Mohammad Khan of Turkestan. This is a clear and picturesque portrayal of the ostentation of the Esfahan court.

– The battle of Chaldoran between the troops of Shah Ismail r Safavid and the Ot-toman Janissaries.

– The reception given by Shah Tahrnasb I in honor of the Hindu prince Homayun who fled to Persia in 1543.

The eastern wall is covered, from right to left. with historical frescos on the following themes:

– The battle scene of Taherabad, in which the armies of Shah Ismail I vanquished the Uzbeks, who, headed by Shibak Khan, threatened the northern borders of Persia (dates to the time when the palace had just been completed).

– Another battle, this time set in Kamal in India and depicting Nader Shah Afshar and Sultan Mahrnud, who is shown on a white elephant.

– The reception given by Shah Abbas II in honor of King Nader Mohammad Khan of Turkestan.

Fortunately, the large frescos have remained almost intact. The small miniatures, however, are in a very dilapidated state. This is mainly because during the Afghan and Qajar periods they were bedaubed with plaster to cover the scenes which were considered to be indecent. During the rule of Zel al-Sultan, the building itself was much threatened, and only due to the interdiction of Malek al-Tojjar, builder of Angurestan-e Malek (p141) and Malek Timcheh (p109), that the governor was talked out of the demolition of the palace.

The Throne Hall is bordered by large rooms on its southeastern and northeastern sides 7, These are also lavishly adorned with beautiful paintings. The hallway leading to the south-eastern room features remarkable gilded ceilings. It is called the Chaharshanbeh-Suri room after a large painting depicting this spring festival.

The exterior galleries 8, of the building exhibit a number of paintings that show the ambassadors and famous Europeans who lived in Esfahan during the Safavid rule. Until recently, little was known about the origin of these paintings. However, it has been determined that these frescoes are the work of two Dutch painters, Angel and Lokar, who were members of the East India Company at the time of Abbas II. One of these pictures may possibly be the portrait of King Charles I of England and his Queen, Henrietta Maria. The other shows an English envoy, holding in his hand a turnip as the Persians always welcomed the gift of unfamiliar plants.

The small but interesting museum of Chehel Sotun, which opened in 1978, contains an outstanding selection of manuscripts, vessels, inlaid and marquetry work, costumes, and fine items of Persian china. The items in the Throne Hall are on permanent display, while those in the smaller rooms, flanking the main hall, are subject to change. Among the most precious objects are the Koran that was once kept above the entrance to the palace; the replica, of the pact signed between Imam ‘id Ali and the Christians; the door from the Mausoleum of Sheikh Safi al-Din in Ardabil and the restored cap of this reverend Sufi; a gilded amulet on deer skin which belonged to Amir Kabir but which seems to have been of little help to the minister who was murdered in Kashan, and the original wooden minbar of the Royal Mosque.

One of the most valuable objects in Chehel Sotun is a stucco window that was brought here from Darb-e Imam (p122). Carved of plaster and studded with stained glass, this unique window is one of the great artistic marvels of Esfahan. Sadly, it is not exhibited to public view and is kept in the museum’s repository.

The garden of Chehel Sotun is also delightful and constitutes part of the museum complex. Remains of some Esfahan’s buildings have been transferred from their original sites to be preserved here. Among them are the portal of the Qotbiyeh Mosque 9, and the portal of Darb-e Kushk 10, Four column bases depicting human and lion figurines, marking the four corners of the large pool, have been relocated from the now demolished Sarpushideh Palace . Another relic includes a dried plane tree, the only remains of Bagh-e Zereshk .