Masjed-e Shah (Imam) O Spr-Sum 8:30 AM — 7:30 PM, AuWin 8:30 AM–15 min before the evening prayer Friday mornings, mourning days

The Royal Mosque (today called the Imam Mosque) dominates the Southern side of Naqsh-e Jahan

Square and is indeed, the most focal point of it. It is the largest and the most magnificent monument of the Safavid reign and is a splendid example of the extravagant architecture that Constituted the glory of Esfahan at that time. We do not Know whether the mosque was called “Royal after its patron, Shah Abbas the Great, or it was just the word to emphasize the mosque’s size and splendor. Both versions are reasonable, all the more so because the Royal Mosque of Esfahan can be claimed the final perfection of the art of mosque building in Iran. The work on this majestic structure was begun in 1611 and lasted for eighteen years. The Sumptuous portal was finished prior to the rest of the building in 1615, completing the imposing Square and offering a counterpart to the Qeysariyeh Portal On the opposite side. Shah Abbas I saw his mosque finished in 1629, the last year of his reign, but the decoration of the building continued even after his death. In 1630 and 1666, some ornamental touches were added to the mosque, but as a whole, the Royal Mosque was an example of a grandiose building created at the behest of One man in One continuous operation. This accounts for the remarkable unity of the decorations, colors, and motifs. Shah Abbas, as if feeling the approach of his death, persistently gave orders for the Work on the building to be sped up. some stories, concerning the construction of the mosque, reflect the haste that accompanied it. One of them tells that Shah Abbas ordered the work on the walls to be started when the foundations had not yet Set. The architect, Ali Akbar Esfahani, refused, and, to avoid the Shah’s anger, went into hiding. When he judged that the time reached to prove his point, he reappeared, demonstrated the accuracy Of his forecast, and was granted the royal pardon. Another story claims that Shah Abbas wanted to save time and money by removing integral blocks from the Congregational i Mosque in Yazd and installing Them in the new building. Fortunately, the clergy, who had a strong impact on the Shah, Were able to persuade him that creating Such a precedent might one day result in his own mosque being similarly desecrated. An important laborsaving innovation employed in the Royal Mosque was the vast usage of polychrome tiles in place of mosaic tilework. In the portal, tesselated faience is applied, but the rest of the surfaces are clothed with polychrome tiles. Except for some sparse use of marble from Ardestan, all the surfaces of the mosque are covered With tiles. The concentration on tile decorations is peculiar to Safavid art, in Contrast to the Seljuk tradition that emphasized the form rather than the decoration. The color of tiles is blue and yellow, contrasting agreeably with the warm tones of marble panels and the stones of the courtyard. It is quite unlike the bright ultramarine of preceding Timurid structures. All in all, there is no other mosque in the city decorated with Such a magnificent blanket of tiles as the Royal Mosque The mosque occupies a total area of 12,264 sq. m. It has been estimated that as many as 18 million bricks and 472,500 tiles were used in the construction of this Safavid marvel. The mosque is based on a four-eivan plan, and consists of multiple sections.

Entrance Portal

The mosque is fronted by a forecourt 1, bordered on three sides by a majestic portal 2, embellished with handsome moqarnas, and the flanking arcades. The area is clearly charged with symbolic meaning: it is a transition from the outer world to a temporal paradise (the forecourt creates the horizontal transition of space, while a portal accomplishes the vertical transition).

The forecourt originally had a pool, but this was closed over at a later date. With two soaring minarets 42 m high and the arch itself being almost 27 m high, the overwhelmingly sumptuous entrance was destined first and foremost to fit in with the square it fronted rather than the mosque itself. A cable ornament, rising from large marble vases, decorates the arch. Flanking the portal are two niches containing reduced versions of the honeycomb decoration

of the vault of the main portal. Above the entrance gateway is a The panel, showing two heraldic peacocks framing a flower vase filled with luxuriant branches. This motif also occurs in the shrines at Ardabil and Mashhad and must have had some special significance, although it is no longer ascertainable. The great calligraphic frieze in Tholth on the portal (dated 1616) specifies that the mosque was built with the personal revenue of Shah Abbas the Great and dedicated to his ancestor, Shah Tahmasb; this is the work of Alireza Abbasi. Below this inscription is another lettering in Tholth, executed by Mohammad Reza Imami, another famous calligrapher of the Safavid period. It testifies to Shah Abbas’s acknowledgement of the architect, Ali Akbar Esfahani, and the construction’s supervisor, Mohib Ali Beikollah. The majestic gold – and silver – plated doors, ornamented with poems written in Nastaliq script, were commissioned by Shah Safi and installed in 1636.

Anteroom

The anteroom 3, as a spatial pivot, interlocks the forecourt and interior courtyard, while making a 45-degree turn. This arrangement allows the aligning of the mosque with Mecca while maintaining the integrity of the square. The plan is similar to the earlier Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, and like there, the visitor hardly notices the change in direction. The effect is contrived by the following architectural trick. The northern eivan 4, instead of having a rectangular ground plan like the other three, ends in a pentagon. It is linked to the anteroom by an arch, a passage through which, however, is blocked by a stone bench that obliges the visitor to make a detour around the north eivan through two vaulted corridors, one on each side, that lead to the court. The right corridor 5, is short; the left 6 is long due to the alteration of the direction. In the anteroom stands a handsome engraved stone vase of great size.

Courtyard

The courtyard 7, measures 3,910 sq. m and is perfectly symmetrical with respect to the axis that points towards Mecca. It is enclosed with twos tory arcades 8, broken in the centers by towering eivrll1s. The ablutions pool 9, in the center measures 240 sq. m. A sense of soaring space strikes the visitor on entering the great court. Once inside, it becomes apparent that the grandeur and scale of the mosque’s layout in no way interferes with the essential doctrinal simplicity of Islam: all the faithful are assured clear and unmediated access to Divine Mercy, and nowhere do they encounter restricted areas, steps or railings.

The Southern Eivan and the Sanctuary

The southern eivan, is usually the most articulated section of Iranian mosques, as it often leads to the main sanctuary. The Royal Mosque also demonstrates a very marked emphasis on the south side. The southern eivan surpasses the other eivans in size and decorative splendors. It is marked by two flanking minarets 11, 48 m high and repeats the decorative motifs of the portal: ogives and stars in lavish gold tones. Behind the eivan is the mosque’s principal sanctuary 12, a square 22.5 m on the side. At its back wall, there are a marble mihrab decorated with mosaics and a fine minbar 4 m high. The minbar is made of a single marble piece and has fourteen steps symbolizing fourteen Shiite saints. The original wooden minbar that was installed here in Safavid times is now kept in the museum of Chehel Sotun. The wall above the mihrab has a niche with the sandalwood doors. Locals believe that the Holy Koran written by Imam Reza and a blood-stained shirt of Imam Hossein are kept there.

The Dome

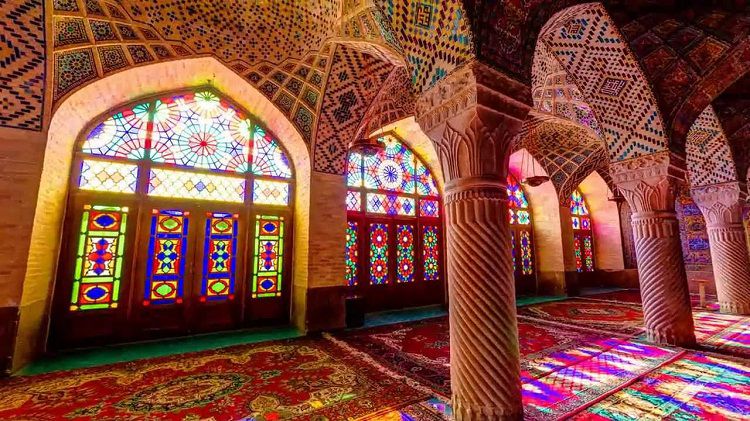

The dome is the most remarkable part of the southern sanctuary. It is 52 m high (the inner shell is 38 m) and about 21 m in diameter.

in diameter. Such dimensions make it the largest twin-shelled dome of Esfahan. The space between the dome’s two coverings is approximately 13 m. This empty space serves as an extraordinary “echo chamber” – since a speaker in the minbar can be distinctly heard in all other parts of the mosque. Check the effect yourself: by stamping on the floor exactly under the dome’s center (marked by dark-colored paving stone) one can hear up to seven clear echoes. The superb dome is an outstanding architectural achievement of Ali Akbar Esfahani. Indeed, if the interior of the sanctuary had been extended to the level of the upper dome, it would have been totally out of proportion. That is why the lower shell was indispensable. On the other hand, had not been this latter crowned by the upper shell, the mosque would have lacked the splendid elevation to which it owes its monumental perfection. The dome has a characteristic bulbous shape and rests on a high drum pierced with eight magnificently partitioned windows. Remarkably, when observed from the interior, the windows seem to open in the curve of the dome; viewed from the outside, they look as if cut in the drum – the ex-planation is that you see two superposed domes. The dome’s interior is dominated by a medallion of a large golden star delicately decorated with roses. The dome features a number of inscriptions; the one around its perimeter, ending with the date 1627, is made by the famous calligrapher Abd al-Baqi Tabrizi. He is also responsible for the inscriptions in the south, north, and west eivans.

Hypostyle Halls

Two prayer halls, topped with small cupolas flank the sanctuary. The cupolas mainly repeat the ornament of the main dome: large golden star and large stylized motifs on a sumptuous carpeting of golden flowers. In the western hypostyle hall stands a huge stone vase with some nicely engraved patterns and a verse in Nastaliq. It was put here in 1683 during the reign of Shah Solei man Safavid.

Eastern

Western Eivans Compared to the south eivan, the facades of the east 14, and west 15, eivans reveal more subtle decoration. The west eivan has a lofty arch surmounted by a maazeneh, from which the faithful are summoned for prayer.

This eivan leads to a large prayer hall that features the mihrab commissioned by Shah Abbas II. This mihrab, perhaps the most beautiful in the mosque, bears an inscription by Mohammad Reza Imami. The walls and ceiling of the western hall are covered with polychrome tiles. Floral motifs n the shades of yellow, blue, mauve, and gold predominate. Almost similar decoration and a similar layout are employed in the eivan and the small hall on the east side.

Madresehs

The Royal Mosque has two madresehs at its southwest and southeast ends. The southwest madreseh 16, known as the Soleimaniyeh Madreseh, was laid out in the end of Shah Abbas’s reign or perhaps during the reign of his successor, Shah Safi. It is, however, named after Shah Soleiman Safavid, who is responsible for repairs, which took place here during his reign. In the courtyard of the Soleimaniyeh Madreseh a triangle stone 17, is placed along the northern wall.

It acts as a sundial for the noon prayer during all days of the year. It is said that, if slightly removed, it would not show the right time. This stone is attributed to Sheikh Bahai, the Safavid scholar.

The southeastern Naseriyeh Madreseh 18, dating from the time of Shah Abbas II, is named after Naser al- Din Shah Qajar, who conducted the repairs of this seminary. The students’ chambers distinguish this madreseh from its counterpart in the western corner. They stretch along one side of the courtyard and overlook the platforms on the opposite side where the students studied.